http://inthesetimes.com/working/entry/after_uaw_defeat_at_volkswagen_in_tennessee_theories_abound

BY Mike Elk

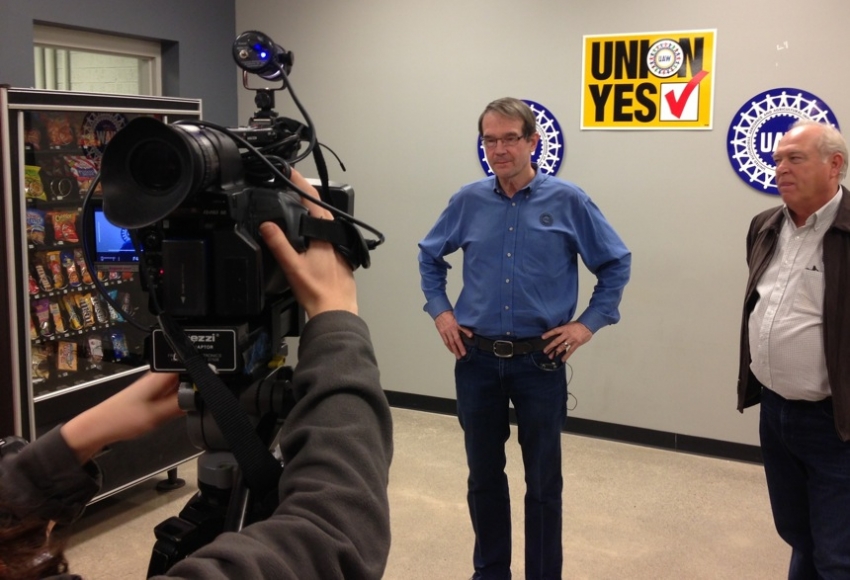

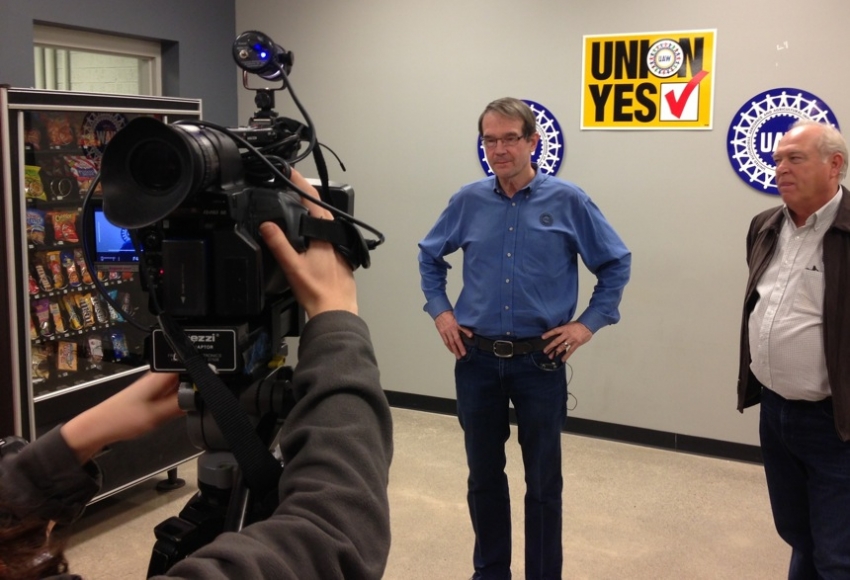

On

February 14, United Auto Workers President Bob King (L) and

Secretary-Treasurer Dennis Williams (R) prepare to respond to the

union's election loss at the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tenn.,

which the UAW blames on interference from right-wing politicians. (Mike Elk)

Workers and organizers cite outside interference, management collusion, union missteps, two-tier agreements and Neil Young

“I am excited,” auto worker Justin King told me as he put on his cowboy

boots to get ready for the victory party planned for late Friday night.

At approximately 10 p.m., the

United Auto Workers union and Volkswagen would announce the results of a three-day union election at the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tenn.

King had reason to be excited. For nearly three years he had campaigned

to get the union into his plant. As one of the leaders of the drive,

his sense was that the UAW had the support of the majority of the

plant’s 1,550 hourly workers. Unlike in most union drives, organizers

didn’t have to worry about the company threatening workers’ job, because

Volkwagen had agreed to remain neutral in the process, so King felt

cautiously optimistic that the support would hold.

But Justin King never got to enjoy his victory party. An hour after we

spoke, retired Circuit Court Judge Samuel H. Payne announced to a

roomful of reporters assembled in a Volkswagen training facility that

the UAW had lost the campaign, with 626 workers voting in favor of the

union and 712 voting against. To the labor reporters, who had seen many

union election results, it was jaw-dropping news. How could a union lose

an unopposed campaign?

Volkswagen signed a 22-page neutrality agreement pledging not to

interfere in the union election at the Chattanooga plant. The company

even let the union onto the shop floor in early February to give a

presentation on the merits of organizing.

It is impossible to say why each of those 712 workers voted against the

union and what the UAW could have done differently to win them over one

by one. However,

In These Times’ interviews with both

pro-union and anti-union workers—as well as low-level Volkswagen

supervisors, top UAW officials and community activists—point to a

confluence of factors, including outside interference by GOP politicians

and unsanctioned anti-union activity by low-level supervisors. Some

questioned, too, whether missteps by the UAW and concerns about its

prior bargaining agreements played a role.

GOP influence

The UAW was quick to blame the loss on public anti-union threats by

right-wing politicians. Immediately following the election results, UAW

President Bob King informed reporters, “We are obviously deeply

disappointed. We're also outraged by the outside interference in this

election. Never before in this country have we seen a U.S. senator, a

governor and a leader of the Legislature threaten the company with

incentives and threaten workers with a loss of product. That's

outrageous.”

Last week, Tennessee’s Republican Governor Bill Haslam

told the Tennessean,

“I think that there are some ramifications to the vote in terms of our

ability to attract other suppliers. When we recruit other companies,

that comes up every time.”

On Monday, two days before the election began, Republican State Senate

Speaker Pro Tempore Bo Watson and Republican House Majority Leader

Gerald McCormick suggested that Volkswagen might not receive future

state subsidies if the plant unionized.

Then on Wednesday, U.S. Sen. Bob Corker (R-Tenn.)—the former mayor of

Chattanooga—who had pledged the previous week not to comment publicly

about the ongoing election,

waded back into the debate

to declare, "I've had conversations today and based on those am assured

that should the workers vote against the UAW, Volkswagen will announce

in the coming weeks that it will manufacture its new mid-size SUV here

in Chattanooga.”

When Volkswagen Chattanooga Chairman and CEO Frank Fischer refuted

Corker, saying the union election would have no effect on the SUV

decision, Corker

doubled down.

"Believe me, the decisions regarding the Volkswagen expansion are not

being made by anyone in management at the Chattanooga plant, and we are

also very aware Frank Fischer is having to use old talking points when

he responds to press inquiries," Corker

said in

a statement on Thursday. "After all these years and my involvement with

Volkswagen, I would not have made the statement I made yesterday

without being confident it was true and factual."

At a press conference following the vote announcement, UAW

Secretary-Treasurer Dennis Williams echoed union president Bob King in

blaming the loss of support for the union on the Republican politicians’

statements.

“When the governor made his comments, we saw some movement at that

time,” said Williams. “When Sen. Corker said he was not going to be

involved and then he came back from Washington, D.C., we had a feeling

that something was happening. Forty-three votes was the difference, so

it’s very disturbing when this happens in the United States of America

when a company and a union come together and have a fair election

process.”

The UAW also announced shortly after the election that it was exploring

legal options and might petition the National Labor Relations Board to

order a new election because of the threats issued by Corker, the

governor and the leaders of the Tennessee State House and Senate.

Opposition at the plant

However, threats of workers losing their jobs are routine during union

elections—though they usually come from management, not outside

forces—and unions still often prevail. Both pro-union workers and

anti-union activists said that other factors played key roles in

derailing the union drive.

While the neutrality agreement forbade Volkswagen from campaigning

against the drive, plant worker and union activist Byron Spencer says

that low-level supervisors and salaried employees—who were not eligible

for the union—ignored the directive and actively opposed the drive. He

also reports seeing multiple low-level supervisors and salaried

employees at the plant wearing “Vote No” T-shirts in the days leading up

to the union election.

Pro-UAW worker Wayne Cliett says there is no doubt in his mind that the

opposition by salaried employees hurt the campaign. “The salaried

people from Pilot Hall [the prestigious research and development center

at the plant] stood out front every day this past week with [anti-UAW]

shirts on, and I truly believe they swayed the votes their way,” says

Cliett.

Indeed,

In These Times interviewed one salaried employee, Mary Fiorello, who actively participated in the

No 2 UAW committee, an anti-union effort organized by a group of hourly workers, who were eligible for the union.

“You have to look at from the point of view of a salaried support

person,” says Fiorello. “My job here is to help them do their job. I

don’t get paid if they don’t make cars, and the union makes it all that

harder. If they want to ask me for help on something and its a union

facility, they can’t even come up and ask me for help. And it makes it

so much tougher for us here to be a team—and we are a team, and it’s

upsetting when a group comes down from Detroit and tells us how we

should be.”

Criticisms of the UAW

The No 2 UAW campaign used the very neutrality agreement that the UAW signed

to argue that the union was making corrupt deals with management without worker input. The anti-union campaign argued that the

neutrality agreement

seemed to indicate that UAW would not bargain for wages above what was

offered by Volkswagen’s competitors in the United States. UAW and

Volkswagen agreed to "maintaining and where possible enhancing the cost

advantages and other competitive advantages that [Volkswagen] enjoys

relative to its competitors in the United States and North America."

"We got people to realize they had already negotiated a deal behind

their backs—[workers] didn't get to have a say-so," hourly plant worker

Mike Jarvis of No 2 UAW told reporters outside of the plant last night.

Fiorello also cited the UAW’s past concessions in bargaining with other

automakers as another example of why she opposed the union. In a

series of contract negotiations

in the late 1990s and 2000s, the UAW agreed to a two-tier wage system

at Volkswagen’s competitors at the Big Three automakers—General Motors,

Ford and Chrysler. Two-tier agreements specify that new hires will earn

significantly less than existing workers. Fiorello notes that currently,

new non-union assembly line workers at Volkswagen start at

$14.50 an hour—which, with cost-of-living differences between Tennessee and the Midwest factored in, is arguably slightly higher than the

just-under-$16-an-hour starting pay under the UAW two-tier contracts at the Big Three.

“See, that’s the kind of problem. Our guys are being paid more than the union [workers at the Big Three],” says Fiorello.

“What the UAW is offering, we can already do without them,” says hourly

worker Mike Burton, who created the website for the No 2 UAW campaign.

“We were only given one choice [of a union]. When you are only given one

choice, it’s BS. It would be nice if we had a union that came in here

and forthright said, “Here is what we can offer.”

“I am not anti-union, I am anti-UAW,” Burton continues. “There are

great unions out there, and we just weren’t offered any of them.”

Burton’s argument seemed to mirror that of Sen. Bob Corker, who

routinely made statements such as, “"It's not about union or anti-union, it's about the way the UAW conducts business."

When asked by

In These Times if the UAW’s history of two-tier

contracts hurt the unions’ ability to win over skeptical workers, UAW

President Bob King responded, “I don’t know. I am not going to speculate

because I wasn’t in the plant.”

Questioned by

Lydia DePillis of the Washington Post

about why the union had agreed to cost-containment measures as part of

the collective bargaining agreement, King responded, “Our philosophy is,

we want to work in partnership with companies to succeed. Nobody has

more at stake in the long-term success of the company than the workers

on the shop floor, both blue collar and white collar. With every company

that we work with, we're concerned about competitiveness.”

Some labor observers have questioned whether provisions in the

neutrality agreement may have also hampered the UAW’s ability to make

its case. “Though neutrality agreements often help avoid vociferous

employer opposition, unions also have to give up powerful organizing or

negotiating tools,” says Moshe Marvit, a labor lawyer and fellow at the

Century Foundation. In the case of the Chattanooga drive, the neutrality

agreement barred the UAW from making negative comments about

Volkswagen. It also specifically prevented the UAW from holding

one-on-one meetings with workers at their homes except at the worker’s

express request. House visits are a common tactic used by union

organizers to build trust with workers and answer questions about

individual needs and concerns. One American Federation of Teachers union

organizer, Peter Hogness, was so shocked that the UAW didn’t do house

visits that he sent me a message today to ask me if it was true.

When asked by

In These Times if the inability to make house visits hurt the union drive, UAW Secretary-Treasurer Dennis Williams simply responded, “No.”

Also, pro-union community activists, who spoke with

In These Times

on condition of anonymity out of fear of hurting their relationships

with the UAW, spoke about difficulties in getting the UAW to help them

engage the broader Chattanooga community. Many activists I spoke with

during my two trips to Chattanooga said that when they saw the UAW being

continually blasted on local talk radio, newspapers and billboards,

they wanted to get involved to help build community support.

However, they say that the UAW was lukewarm in partnering with them. Indeed, when I attended a forum in December organized by

Chattanooga for Workers,

a community group designed to build local support for the organizing

drive, more than 150 community activists attended—many from different

area unions—but I encountered only three UAW members. Community

activists said they had a hard time finding ways to coordinate

solidarity efforts with the UAW, whose campaign they saw as insular

rather than community-based.

“There’s no way to win in the South without everyone that supports you

fighting with you,” said one Chattanooga community organizer, who

preferred to remain anonymous. “Because the South is one giant

anti-union campaign.”

A harsh Southern climate

Still, at the end of the day, unions make missteps in union elections

all the time and often face opposition from management, and the workers

still sometimes win. Indeed, the NLRB reports that unions won

60 percent of elections conducted in fiscal year 2013. So why didn’t the UAW win in Chattanooga?

“We thought we had the number we needed,” says Cliett. “We could

analyze for days and not really know for sure, but I do think the last

minute blitz of negative campaigning from our politicians turned some

votes to no. What is going on with these people? Lynyrd Skynyrd may not

have liked the song written by Neil Young, ‘Southern Man,’ but Neil had a

point.”

In the 1974 song “Sweet Home Alabama,” Ronnie Van Zant of Lynyrd

Skynyrd sings, “Well I hope Neil Young will remember: A Southern man

don’t need him around anyhow.” The lyric is a reference to Canadian

singer Neil Young’s “Southern Man,” which criticized Southerners for

being opposed to social change.

But for one Southern man, progress still feels achievable. “I'm a

stubborn man,” says Cliett. “Some are talking about quitting. I will be

walking into the plant on Monday with my head held high and preaching

the message of solidarity.”

Full disclosure: The author’s mother worked on an auto assembly

line at a VW plant in Westmoreland County, Pa., until it closed in 1988,

and was a member of UAW. UAW is a website sponsor of In These Times.

Sponsors have no role in editorial content.

One

of the most confusing aspects of the last decade’s education reforms is

that a reform that will do great harm often contains an element that’s

useful, even progressive. The reforms are crafted to seduce liberals

with this combination of a carrot and grand rhetoric about the intention

of increasing educational opportunity. Testing was sold to liberals as

a way to hold schools accountable. Now a national curriculum, the

Common Core, is being peddled as essential to give all students the

rigorous education (they love that word “rigorous”) they need to compete

in a global economy in the 21st century.

One

of the most confusing aspects of the last decade’s education reforms is

that a reform that will do great harm often contains an element that’s

useful, even progressive. The reforms are crafted to seduce liberals

with this combination of a carrot and grand rhetoric about the intention

of increasing educational opportunity. Testing was sold to liberals as

a way to hold schools accountable. Now a national curriculum, the

Common Core, is being peddled as essential to give all students the

rigorous education (they love that word “rigorous”) they need to compete

in a global economy in the 21st century.